Preeclampsia is one of the most serious complications of pregnancy, affecting about 8% of first-time mothers. It causes high blood pressure, protein in the urine, and blood vessel damage, leading to severe risks for both mother and baby. Each year, preeclampsia accounts for more than 46,000 maternal deaths and 500,000 infant deaths worldwide, and it increases a woman’s risk of developing cardiovascular disease later in life [1].

Preeclampsia is one of the most serious complications of pregnancy, affecting about 8% of first-time mothers. It causes high blood pressure, protein in the urine, and blood vessel damage, leading to severe risks for both mother and baby. Each year, preeclampsia accounts for more than 46,000 maternal deaths and 500,000 infant deaths worldwide, and it increases a woman’s risk of developing cardiovascular disease later in life [1].

Despite its impact, the exact causes of preeclampsia remain unclear. For decades, the placenta was considered the main culprit. However, recent research has revealed that defects in the endometrium (the uterine lining) persist for years after preeclampsia, pointing to a strong maternal contribution [2]. In addition, increasing evidence indicates that the immune system plays a central role in how the uterus responds during pregnancy [3].

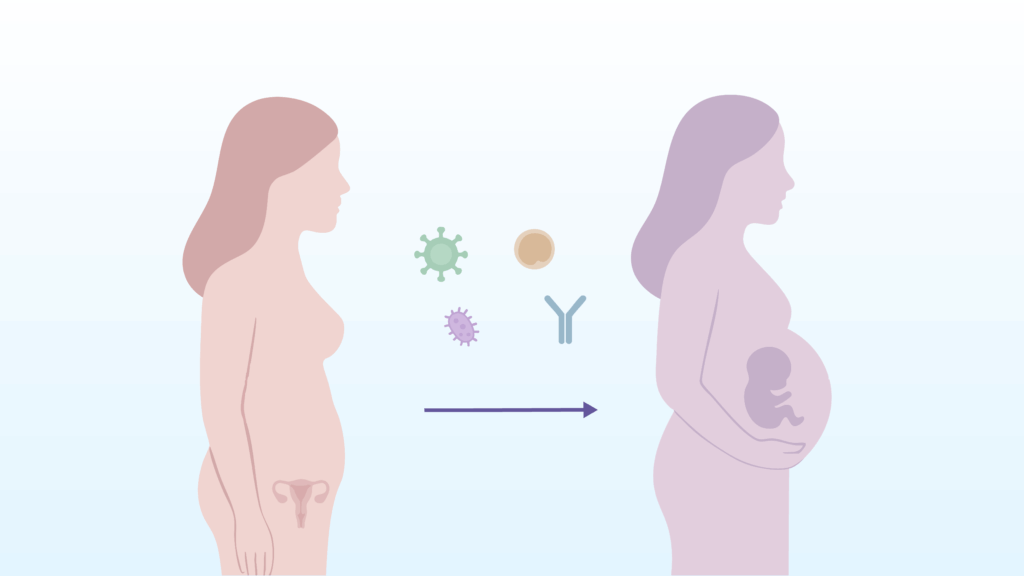

The PREMIC project, led by Dr. Maria Cristina Carbajo Garcia at the Carlos Simon Foundation and the University of Valencia and supervised by Dr. Carlos Simon, Dr. Tamara Garrido Gomez, and Dr. Inmaculada Moreno Gimeno, is a multi-institutional initiative supported by the PROMETEO 2023 program of the Regional Ministry of Innovation, Universities, Science, and Digital Society of the Generalitat Valenciana. PREMIC investigates whether microbial exposure and immune responses could be the missing link in preeclampsia. The hypothesis is that past microbial infections may trigger long-lasting inflammation in the endometrium and immune alterations, leading to abnormal decidualization and vascular damage (two hallmarks of preeclampsia).

This line of research is inspired by what we know from other conditions: infections such as Epstein-Barr virus or COVID-19 can leave behind chronic effects, raising the risk of multiple sclerosis or cardiovascular disease years later [4,5]. These findings have reshaped how we think about infections: not only as short-term illnesses, but as events that may reprogram our tissues and immune system for years to come. PREMIC builds on this concept to examine whether similar processes occur in the uterus and whether they could underlie the origins of preeclampsia.

If this connection is confirmed, the implications could be transformative. Detecting and treating infections before or early in pregnancy may reduce the risk of preeclampsia, while new therapeutic strategies could target inflammation and immune-driven pathways that damage maternal vessels.

By exploring the infectious and immunological origins of preeclampsia, PREMIC is not only advancing our understanding of this complex disease but also moving us closer to early diagnostic tools and preventive strategies that can make pregnancy safer.

References:

1. World Health Organization. Preeclampsia. April 4, 2025. Accessed September 9, 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/pre-eclampsia

2. Muñoz-Blat I, Pérez-Moraga R, Castillo-Marco N, Cordero T, Ochando A, Ortega-Sanchís S, Parras-Moltó M, Monfort-Ortiz R, Satorres-Perez E, Novillo B, Perales A, Gormley M, Granados-Aparici S, Noguera R, Roson B, Fisher SJ, Simón C, Garrido-Gómez T. Multi-omics-based mapping of decidualization resistance in patients with a history of severe preeclampsia. Nat Med. 2025 Feb;31(2):502-513. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-03407-7. Epub 2025 Jan 7. PMID: 39775038; PMCID: PMC11835751.

3. Saito S. Role of immune cells in the establishment of implantation and maintenance of pregnancy and immunomodulatory therapies for patients with repeated implantation failure and recurrent pregnancy loss. Reprod Med Biol. 2024 Aug 1;23(1):e12600. doi: 10.1002/rmb2.12600. PMID: 39091423; PMCID: PMC11292669.

4. Bjornevik K, Cortese M, Healy BC, et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science. 2022;375(6578):296-301. doi: 10.1126/science.abj8222.

5. Xie Y, Xu E, Bowe B, Al-Aly Z. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2022 Feb 7]. Nat Med. 2022;10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3.